The Man Who Refused to Die

My great-uncle survived Bataan, torture, and war itself — but his greatest act was forgiveness.

Every family has stories that seem larger than life — the kind that sound almost too extraordinary to be true until you realize they actually happened to someone you’re related to. For me, that story belongs to my great-uncle, Arthur Lansing “Lu” Campbell — though everyone in my family just called him Uncle Art.

Uncle Art was the oldest boy in a family of ten kids. Three of his siblings died as babies, and like a lot of boys growing up in tough times, he wanted to see the world. At just sixteen, he lied about his age and joined the U.S. Army. They put him in the Air Corps and taught him to fly. It was there, in the Philippines, that he was stationed when the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor — and his world, like the world itself, changed forever

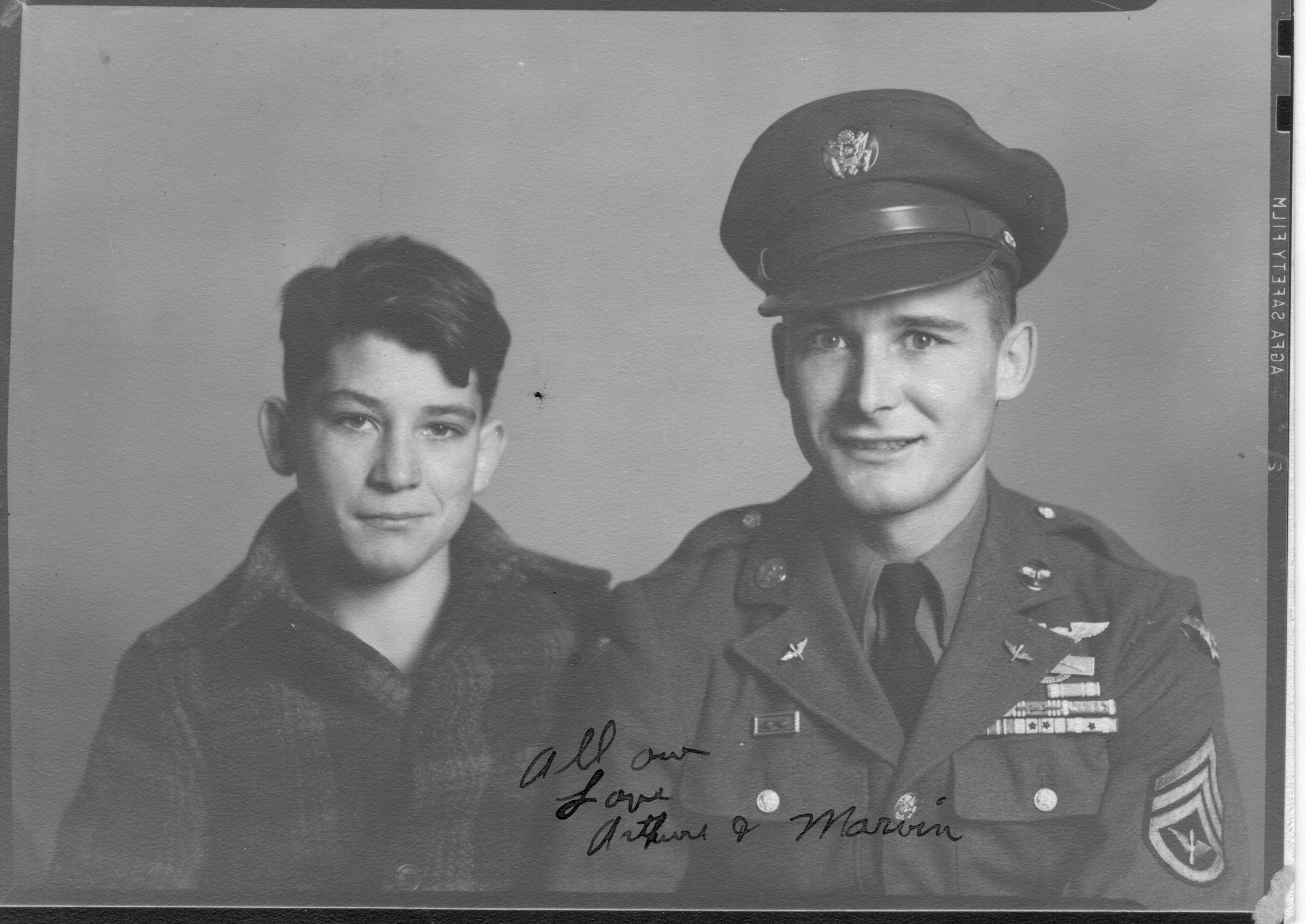

My Grandpa Marvin Campbell and his older brother Arthur Lansing ‘Lu’ Campbell. This is after he had returned from war and was healed up.

He spent the entire war in the Pacific, caught up in some of the most brutal chapters of World War II. He survived the Bataan Death March and became a prisoner of war. He tried to escape multiple times, but each time he was captured and punished. The Japanese used him as a test subject for disease-control experiments. He was hung by his thumbs, frozen and thawed, infected and “treated,” had his teeth pulled and replaced with wooden ones. It’s almost impossible to comprehend what he endured — and even harder to imagine the strength it took to survive it.

The Bataan Death March where nearly 80,000 American and Filipino soldiers had to walk 65 miles with almost no food or water. If you collapsed the Japanese soldiers shot you.

During one of his work details, Uncle Art and a group of prisoners were marched back into camp after hours of chopping through the jungle under the watchful eyes of their Japanese captors. When they entered the camp, they saw a wooden cross where a young Filipino woman had been stripped naked, tied, and hung. Without thinking, Uncle Art reached up and cut her down.

When he woke the next day, he was hanging naked on that same cross. The guards were ready to kill him when he shouted, cursed, and spat at them with a fury that startled everyone. The Filipino prisoners, desperate to save his life, told the guards he was possessed by Lucifer — and the superstitious Japanese, fearing the devil, cut him down and let him live. From that day forward, the men called him “Lu,” short for Lucifer — a nickname that stayed with him for the rest of his life. It wasn’t a mark of evil; it was a mark of survival.

Eventually, he was freed — by a Russian soldier — and for a time, he fought alongside the Russians, driving tanks as the war wound down. They respected his courage so much that they awarded him a medal — something extraordinarily rare for an American soldier at the time. To be recognized by the Russians, who had lost millions of their own in that brutal conflict, spoke volumes about the kind of man he was.

When the war finally ended, he was sent home on a ship that hit a mine. He floated in the water for days before being rescued.

When he came home, he was skin and bones, a shadow of the young man who had left years earlier. He hadn’t been around civilization for so long that even the simplest comforts — food, light, the feel of clean sheets — felt foreign. The nurse assigned to help him recover was a young girl who saw past the trauma to the man underneath. She later became his wife.

Francis and Arthur Campbell

Uncle Art had been officially declared dead during the war, and for years, the record still listed him that way. It took time and effort — even after everything he’d survived — to prove to the U.S. government that he was, in fact, alive. It’s almost poetic, really: a man who refused to die even when the world had already written him off.

During his captivity, there was a Japanese guard who made his life miserable. Uncle Art swore that if he ever got the chance, he’d kill that man — and during the chaos of war, he did. Uncle Art was ruthless and lived up to his nickname. Years later, at a reunion for former prisoners of war, he met someone else: another American soldier who had once betrayed him. That man had ratted out an escape plan, costing Uncle Art and several others their freedom and subjecting them to brutal punishment.

When the two men unexpectedly found themselves in the same elevator years later, the tension was thick. The man recognized Uncle Art instantly and froze. He knew what he had done and he knew Art’s nickname. Uncle Art could have held onto his anger — but instead, he extended his hand, and told him he forgave him. Both men cried.

That moment — that choice — says as much about his heroism as any medal ever could. And he had plenty of those too: the Presidential Citation for Valor, three Purple Hearts, the Bronze Star, the Silver Star — and that Russian medal, gleaming with a meaning few could ever understand. But it’s the humanity behind the heroism that sticks with me most.

After the war, he didn’t seek fame or fortune. He did play poker with Baby Face Nelson once. He managed a JCPenney auto department. He lived a quiet life — not what the world would call “grand,” but grand all the same. His life was rich in courage, humility, and grace.

I wish I had more of his stories written down in his own words. The fragments we have — told at reunions, passed through generations — feel like treasures. But there’s so much we’ll never know. Uncle Art passed away February 18th, 2009.

And that’s really what I want to say this Veterans Day.

We owe a debt to our veterans — not just of gratitude, but of memory. Their sacrifices built the world we live in, and yet so many of their stories are fading with time. We can’t let that happen. We can’t take them for granted.

So here’s my challenge: this week, thank a veteran. Hug them if you can. Ask them about their story — and then write it down, record it, or capture it somehow. It doesn’t have to be fancy. With technology today, there’s no excuse. You can talk into your phone and have it typed for you. There are apps, programs, and even AI tools that can help preserve voices and memories for future generations.

And while you’re at it — tell your own story too. You don’t have to wait until it’s polished or perfect. Just start. You’ll figure it out as you go. The point is to begin before the moments fade.

My Uncle Art lived a life of extraordinary courage and quiet redemption. He proved that even in the darkest places, light can endure — and even after the worst cruelty, forgiveness can still triumph.

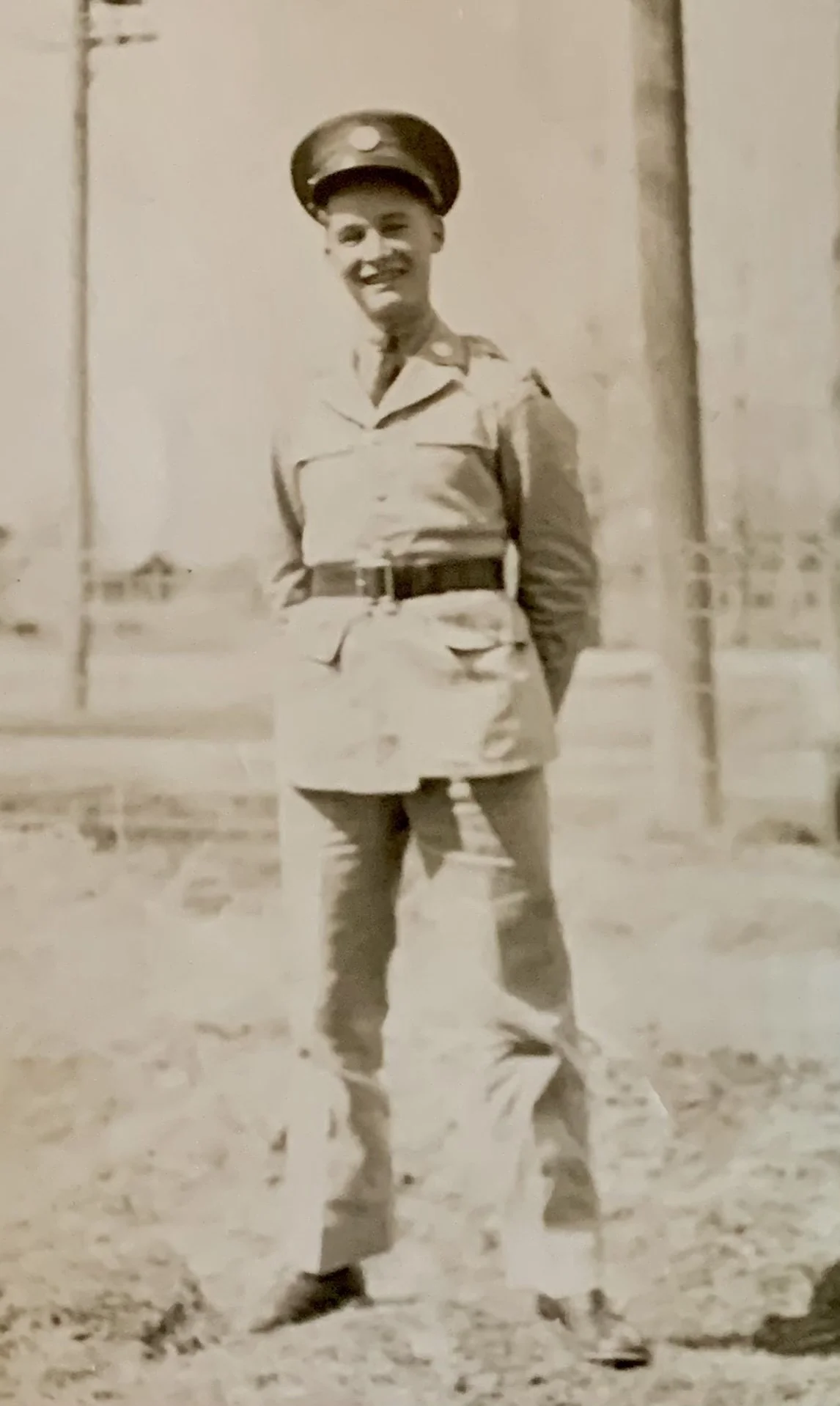

Arthur Lansing ‘Lu’ Campbell

May we honor him, and all veterans, not just with parades or words, but by remembering who they were and what they stood for. And may we keep their stories — and ours — alive.